Interview with Christopher Curtis Sensei by Online Magazine “Martial Arts of Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow”

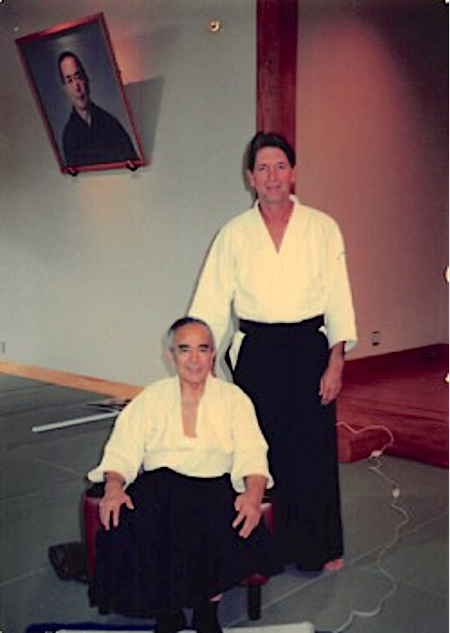

Christopher Curtis first encountered Aikido through a meeting with Yoshimitsu Yamada as part of a theatre group. Later, after participating in a three-year meditation retreat, he found his lifelong instructor Shinichi Suzuki and quickly joined the Maui Aikido Dojo. Staying with Suzuki, Curtis had the opportunity to train in Japan at the ()/Ki Society Honbu with Koichi Tohei and Iwao Tamura. In 1998, Tohei made him Chief Instructor of the Hawaii Ki Federation. Today, Curtis took some time to talk about his incredible Aikido journey, his meetings with Koichi Tohei, the personal relationship with Suzuki, and Aikido’s history in the Hawaiian Islands. All images provided by Christopher Curtis.

Martial Arts of Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow: Hello and welcome Curtis Sensei! We look forward to our discussion about Hawaiian Aikido!

Christopher Curtis: Thank you for having me! I look forward to it as well.

MAYTT: You were first introduced to Aikido in a chance meeting with Yoshimitsu Yamada. How and when did you come to find Yamada and what were your initial reactions to Aikido?

CC: This meeting was in the spring of 1969. At that time, I was a professional actor working with Joseph Chaikin’s “Open Theatre” in NYC. We were working on an original production of a play by Jean-Claude van Itallie, and it included some very intricate movement sequences. Mr. Chaikin had the idea to bring in Yoshimitsu Yamada Sensei to help us with these movements. At that time, Koichi Tohei Sensei was the Chief Instructor of the Aikikai Hombu in Japan, and so Yamada Sensei was his direct student. What Yamada Sensei shared with us that day were many of Tohei Sensei’s principles of unification and relaxation in movement. This teaching was unique, and completely new to me, and extremely useful. I was a founding member of the California Shakespeare Festival, and in addition to acting, I was the principal choreographer of foil, epée, rapier and dagger, sword and buckler, and broadsword sequences called for in Shakespeare’s plays. I had learned the use of these weapons at Carnegie Mellon University, as well as dance, general stage movement and presence, so this idea of complete relaxation in movement made a deep impression on me. At the time, I remember wondering how it was possible that this understanding was not a part of any of the regular curriculum in any university.

possible that this understanding was not a part of any of the regular curriculum in any university.

MAYTT: You later went on a three-year meditation retreat, which seemed like a catalyst for you to ultimately meet Shinichi Suzuki and move to Maui. Could you tell us how you came to meet Suzuki Sensei and move to Maui?

CC: What had originally motivated me to become a professional actor was my yearning from a young age to understand the deeper motivations of human beings. Why do we allow preference and aversion to so totally dominate our lives, both of which are the source of all suffering, if we don’t like suffering? My time in the meditation retreat naturally addressed this question. However, unless I was to spend the rest of my life as a monk, I needed to find a way to practice what I had learned in a much more practical, everyday kind of way. I asked my meditation teacher at the time, and he suggested I find some kind of “Zen-based martial art” to practice.

By 1974, I had married and moved to the island of Maui. One night I went to a local Buddhist Hongwanji to hear a Tibetan teacher speak. Afterwards, I went backstage to thank him. The local Buddhist priest spoke to me, asking if I was interested in the practice of Buddhism. I answered that I was, but that what I really was looking for was a “Zen-based martial art.” At this point, I still did not connect this as related in any way to what I had learned of Tohei Sensei’s teaching through Yamada Sensei. The priest immediately said to me, “Then you are in the right place. Just up the street in the town of Wailuku, is the Maui Aikido Dojo, and the instructor there, Shinichi Suzuki Sensei, happens to be the top guy in the world outside of Japan.

The next day I signed up. Suzuki Sensei was then still training with Tohei Sensei in Japan, and so for the first six months of my aikido training, I was with one of Sensei’s assistants. In the fall of 1974, Suzuki Sensei returned to the Maui Aikido Dojo. My first class with Suzuki Sensei was completely unexpected. By this time, I had read a little about this relatively obscure art of aikido, and I imagined my teacher would be a rather quiet man, small in stature, retiring, and very “spiritual,” with a loving look that would awaken me to the secrets of the universe. Instead, Sensei stepped onto the mat with a loud, “Hello Fellas!” and proceeded to pick up a bokken and chase us into the corner, yelling at us that we were not taking life seriously enough. “This is ‘shinken shobu,’ life and death training! You must be completely present in every moment!” Unsurprisingly, Sensei’s nickname at the Headquarters in Japan had been “Thunder Lips.”

I was with Suzuki Sensei from 1974 until his passing in 2009. For most of those years I was actively his otomo – humble assistant. Of course, there are many tales to tell. If anyone is interested, many of those stories and much more about the character of this great teacher are included in one of my books available on Amazon, Otomo – A Journey.

MAYTT: I see. How would you describe the training you experienced when you first started Ki-Aikido? How have you seen Ki-Aikido change and evolve up to today?

CC: In my personal experience, the most notable change has been a moving away from the belief that if we are to awaken to the secrets that this universe has to offer us, we must suffer. During the time that Aikido was becoming established as a martial art in Japan, before, during, and after World War II, this kind of understanding was still very prevalent throughout the world. In some countries, we are slowly moving beyond this, though in many, this parochial idea persists. Sad to say, largely in the world of martial arts, and even in much of Aikido as it is taught and practiced today, this attitude prevails.

Along this line, during the later years of both Tohei Sensei’s and Suzuki Sensei’s teaching, there was a clear evolution from a rather harsh and demanding approach to the practice, to a much softer, more relaxed, and much deeper approach. Part of this change has been necessary simply to meet the changes taking place in the world around us. If we tried to run a dojo today in the same way that it was run in the early days of Aikido, no one would come to train with us. That said, we at the Maui Shunshinkan Dojo have continued with a very traditional approach to instruction.

MAYTT: You also worked in theatre, being responsible for choreographing sword fights. How did that experience help you with your Ki-Aikido training and vice versa?

CC: Frankly, when I first came to Aikido practice, I imagined that I had a clear understanding of the use and treatment of bladed weapons. It took only a few months of bokken, tanto, and jo training with Suzuki Sensei and Tohei Sensei to realize just how ignorant I was of any () real connection with this kind of practice.

The fundamental principle taught by Koichi Tohei Sensei has always been “mind leads body.” In a past interview, someone once asked me: “Has your perception of Aikido changed throughout the many years you have been practicing Aikido?” I answered: “Certainly. In the beginning, I thought it was about movement of body. Then, I saw it as movement of mind. Now, I cannot discover a difference.”

MAYTT: With that in mind, how different was your understanding of Western weapons and their mechanics to what both Suzuki and Tohei taught you about Japanese weapons? Was there really no overlap between the two sets of cultural weapons that ultimately forced you to relearn how to use a weapon?

CC: This is a very good question. In my training with Suzuki Sensei, I did not discover any fundamental difference between the use of Western weapons as opposed to Eastern weapons. In training with any weapons, as with any other skill, we begin with learning form. Once we have grasped and perfected that level, we often think that we have reached mastery. However, nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, to think of ourselves this way is a kind of barrier to mastery. As an example, let me relate a story from my book, Otomo – A Journey, that I think exemplifies this point.

During the middle years of my training with Suzuki Sensei, we would meet at the dojo each afternoon at 5:00 pm. The regular classes began at 7:00 pm, which gave us more than an hour to practice together on our own, before others arrived. During these years, Suzuki Sensei would cut bokken (the wooden practice sword) with me each day in front of the mirror in the dojo. This was just one very simple straight cut, from “jodan” to the “chudan” position. Nothing fancy. First, he would cut, then I would cut, and as this progressed, my skill level naturally became better, and better, and better at cutting. After just a couple of years, I felt I was getting what it really meant to hold the bokken lightly, as if one was holding the whole universe in one’s hands. I worked doggedly at finding the center point on the scale of cutting with a kind of wild power and then cutting with precise control. I imagined I was getting closer and closer to that center, that perfectly balanced cut, and the seemingly endless repetitions were sure to bring me ever closer to the illusive point of perfection, no matter how many years it took. Nonetheless, he continually told me, “No, this is still not correct cutting. You must let go of cutting correctly.” In spite of this instruction, the “correct cut” remained my obsession, and I was convinced that the correct cut must lie right in that midpoint on a scale of too much freedom on the one end, and too much control on the other. I relentlessly clung to this notion like a drowning man clinging to a life raft. I had no idea that what he was looking for was something else altogether, something completely outside the realm of the relative world view, a state of mind where such measurable scales cease to exist entirely.

When others saw me cutting in those days, they would often remark at how expert I had become. This made me feel very good, of course. But my teacher just kept saying, “No, that’s not it!” I began to be a little confused. I couldn’t figure out what the heck was going on, because as far as I could tell, I was getting really good at this cutting of the bokken, always coming closer and closer to perfection. And still, Suzuki Sensei said, “No! You don’t understand AT ALL!” Not, “You are almost there; you have almost got it. Keep going.” You know, encouragement. There was nothing like that. He said I didn’t get it “at all,” that I was completely missing the point. Can you imagine? This was a great mystery to me.

This process, always including these afternoon dojo sessions with Sensei, went on for approximately fifteen years. And constantly, he repeated after each of my expert cuts, “No, that’s not it. Please let go of cutting. Cut again.” After this prolonged period of time, I was beginning to feel a bit disheartened, as you can imagine. What did he mean? “Let go of cutting.” Of course, I could hear that he seemed to be telling me that I had to somehow let go of the act of cutting correctly, but wasn’t that what we were so compulsively engaged in, cutting correctly?! Come on, man, you can’t have it both ways. Or can you?

Finally, I remember one Wednesday morning waking up feeling very down about this entire exercise in, what seemed to me to be, futility. There had been some slippage going on for some time. My goal of achieving this “one true cut” was becoming a little vague, no longer clearly set out there as a defined objective.

As I sat through my early morning meditation that day, I began to become more and more angry at my teacher. Why did he not see how much I needed the encouragement that he so freely seemed to shower on all his other students? As the day rolled on, I found my anger increasing, and so seemingly impossible to let go of. I even decided, at several points, just to stay home that afternoon, and forget the whole thing. Of course, after all of those years of stubborn effort, together with the inherently deep respect I held for my teacher, I could not bring myself to do that. So, I departed for the dojo at the regular appointed hour. As I drove to the dojo that afternoon, I began to notice a shift in my emotions. The closer I got to the dojo, the more I began to feel that the whole cutting thing was simply hopeless, and that there was really nothing more for me to discover about cutting the bokken. This realization somehow gave me just a fleeting glance at a mysterious feeling or awareness of something inside somewhere, straining to emerge. I didn’t know what it was, but it was in me, and it was alive, and it was powerful.

I arrived at the dojo in a state of mind completely devoid of hope or promise of any kind. I knew I had given up my goal. Knowing this did not depress me, it did not make me feel any particular way. It was like I was in a kind of “in between” place, emotionally.

I changed clothes into my training gi, and, completely empty of any specific feeling, I met Suzuki Sensei on the mat, bowed in greeting, and picked up the bokken. Turning towards the mirror, instead of waiting for him to set the pace by cutting first, I simply cut fully, just once. Suzuki Sensei exclaimed, “That’s it! Now do it again.” Smugly, I cut again, repeating what I thought was the exact same cut. “No, that’s not it.” The shock of hearing his positive response to the first cut had elicited such a self-congratulatory emotional download in me, that the second time I cut was crammed full of my own pride of accomplishment. The compulsively desperate desire to achieve was suddenly and miraculously reborn in me! Thus, naturally, this was not “it.”

Following this singular event in my training life, we continued for approximately four or five more years of these meetings, cutting together as before. Now, however, as the true understanding and appreciation of what my teacher had awakened in me sank deeper and deeper into my mind and body, more and more often he would say, “Yes, of course. You are understanding.” Then, finally, one day Suzuki Sensei simply nodded and said to me, “OK, now you know. You can now teach bokken any time to anyone with my blessing.”

Mastery in weapons cannot be taught. It is entirely up to the student. Of course, it helps to have a teacher with great patience!

MAYTT: That was quite the experience! You have had the privilege to train under three prominent and highly skilled Ki-Aikido instructors: Koichi Tohei, Shinichi Suzuki, and Iwao Tamura. How did these instructors compare with each other in terms of instructional methods, technique application, and personalities?

CC: Well, first and foremost, Suzuki Sensei and Tamura Sensei were both ninth dan, and devoted students of Tohei Sensei, so their teaching largely echoed their teacher’s approach to instructional method and technique application. However, in terms of personality, they were very different.

For Tohei Sensei, particularly in the last twenty years of his life, it was difficult to get close to him. I was very fortunate in being Suzuki Sensei’s otomo and primary student. Because Suzuki Sensei was Tohei Sensei’s closest foreign student and friend, whenever in Japan or Hawaii, the two of them spent much of their time together. And since I was Suzuki Sensei’s otomo, I went most places with him, and so was able to get to know Tohei Sensei quite well off the mat, as it were. He was always very gracious and kind. Even when, on one occasion, his wife was very upset and yelling at him about something, I remember looking at Tohei Sensei and him smiling kindly and giving her his full attention. He always practiced what he preached.

Suzuki Sensei had a huge heart, and a great sense of humor. He loved to play practical jokes on everyone, though he could be strict as well, particularly with me. Once I asked him, “Sensei, why is it that you seem so kind and forgiving to everyone else in the dojo, but you are so strict with me?” He said, “Because you need it.” He told me many years later that he did not mean that I was stupid or unruly in any way, but that he knew even in those early days that I would someday become the Chief Instructor of Maui, and then of Hawaii. How he could have known that would come to be, so long ago, must remain a mystery. Suzuki Sensei was also quite formally traditional and insisted again and again that I carry on the many rituals surrounding our dojo practice after he was gone.

Iwao Tamura Sensei was a completely unique individual. During the early days of training in Japan, I was often a lonely Caucasian in the Ki no Kenkyukai Headquarters Dojo in Tokyo and found it difficult to understand some of the obscure aspects of Japanese culture. Tamura Sensei took me under his wing. He had worked as a helicopter mechanic during the US Occupation of Japan after the war, and so spoke English fluently and with almost no accent. Sensei was amazingly supportive of me, both on and off the mat. He loved to drink and talk aikido with me, and we often spent long into the night after practice in his dojo in Kanagawa, as he kindly put to rest much of my bewilderment regarding this strange culture I was getting to know.

MAYTT: What impactful lessons did Tohei, Suzuki, and Tamura that stuck with you for the rest of your training?

CC: Koichi Tohei: “The purpose of our practice is to be one with the universe.”

Shinichi Suzuki: “Never tell a student not to do something, but only show him what to do.”

Iwao Tamura: “Universal mind always recognizes itself.”

The fact that these three quotes are what I remember and cherish most about these three great teachers, certainly reflects what I value most in this practice.

MAYTT: Suzuki was one of the mainstays of Hawaiian Aikido. Could you tell us more about him?

CC: During and even after World War II, the Japanese American people living in Hawaii, just as in other parts of the US, were treated with suspicion and often even derision. Most were sent to internment camps, but the few that had positions that were essential, like police officers, were allowed to keep their jobs. The response by the Japanese American community to this racial bias and prejudiced treatment was naturally equally strong. This meant that any person or group of Japanese heritage that excelled in any way, was strongly celebrated by the Japanese American community. Suzuki Sensei was a Maui police officer during the war whose beat was on streets that were daily filled with soldiers on leave from fighting the Japanese army, navy, and air force throughout the Pacific Theatre. During those difficult years, Suzuki Sensei was disparaged for wearing the Maui Police uniform almost daily and was forced to physically defend himself and/or others, often with more than one soldier at a time. Sensei was a judo player in those days, and he told me, because of his judo training, he was able to take on up to three soldiers at a time, but more than three, and he was usually done for. “Oh,” he would say to me later, “if I only had met Tohei Sensei before that!”

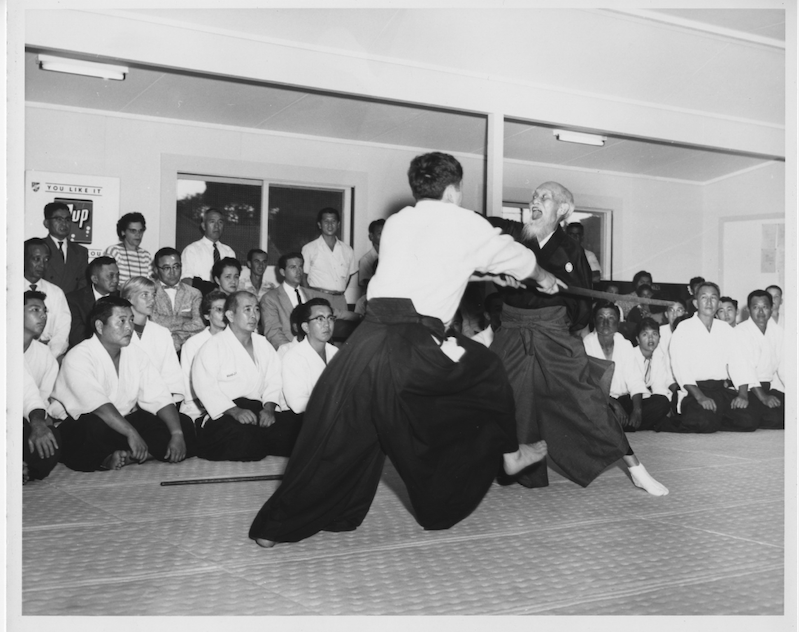

Of course, his actions during the War made Suzuki Sensei a hero on Maui even before Aikido. Not so long after the War, in 1953 Morihei Ueshiba Sensei sent Tohei Sensei to Hawaii to begin the spread of Aikido in the west. As a Maui police officer of Japanese descent, Suzuki Sensei was assigned to look after Tohei Sensei during his stay on Maui. It was during this time that Tohei Sensei had been featured on the Pathé News, as he single-handedly defeated the entire US Judo team at once, showing the effectiveness of his Aikido for the first time in the west. Suzuki Sensei had seen this on the news and immediately upon meeting Tohei Sensei, became his student. Suzuki Sensei was made the first Chief Instructor of the first Maui Aikido group, which just added to his esteem in the local community here.

By the time I arrived on Maui in 1972, the general post-war negativity towards the Japanese had reduced considerably, but for the Japanese American community, there remained much to prove. This meant that a person with the kind of charisma and reputation that Suzuki Sensei had, together with his experience of spending so much time in Japan with Tohei Sensei, combined to make him extremely well-known and popular statewide.

In 1974, I was fortunate to meet him at exactly the right moment in time.

MAYTT: That is an interesting turn of events. Who else would you consider to be a Ki-Aikido pioneer in Hawaii? What differentiated them from their contemporaries?

CC: The other major Ki-Aikido teachers in Hawaii during that period were Takashi Nonaka Sensei from the Big Island of Hawaii, and Seishi Tabata Sensei and Harry Eto Sensei from the island of Oahu. Like Suzuki Sensei, these three individuals began training with Tohei Sensei very soon after 1953 when he first arrived in Hawaii. And they also spent a good deal of time training with Tohei Sensei in Japan and were his primary hosts when he visited each of their Hawaiian Islands.

In those days, outside of Japan, Hawaii was truly the “Mecca” of the Ki-Aikido world. Through the years, as Ki-Aikido took hold in other countries, many students would come to experience what these famed local instructors from Hawaii had to offer. By that time, the fact that they were of Japanese descent was a big plus for their credibility, not just locally, but throughout the world.

MAYTT: You are also the Chief Instructor of the Hawaii Ki Federation. How did you come to assume such a position and responsibility? How do you feel the Federation has helped solidify Ki-Aikido in Hawaii?

CC: From 1974, the Ki-Aikido group in the state of Hawaii was known as the “Hawaii Ki Society.” Up until the year 2000, there were separate Ki Societies on each of the four major islands, and each had their own primary Chief Instructor.

In October 1998, I was staying at the Ki-Aikido Headquarters in Tochigi-ken, Japan, and training with Koichi Tohei Sensei. One evening, Tohei Sensei invited me to visit him at his home near to the Headquarters complex. During this visit, Tohei Sensei said to me, “Curtis-san, I would like you to form a new Hawaii state-wide Ki-Aikido organization. This time, I want to eliminate politics as much as possible. We will call the new organization the ‘Hawaii Ki Federation.’ This new organization will be a federation of dojos spread throughout the state, with no longer any emphasis on the different islands, or their previous Chief Instructors. You will be the only Chief Instructor, and each dojo will have a Head Instructor confirmed or assigned by you. I want you to teach as I teach and provide consistent support and qualified instruction to all who are members, regardless of their previous loyalties.” This was a bit of a shock, since, at that time, all the original main Hawaii sensei were senior to me, most significantly my own instructor Shinichi Suzuki Sensei, and were still living and actively teaching! How could I possibly presume to take over as the Chief Instructor of the State? “Never mind about that,” Tohei Sensei said. “I will speak to each of them and explain that I would like to have this new Hawaii organization headed up by a younger person, someone who will still be able to hold the group together long after they have passed on.”

I have been the Chief Instructor of the Hawaii Ki Federation for the past twenty-two years, and for an unbiased observation of how effective I have been with the responsibility, you must ask my students. For me, I continue to be very grateful to be allowed to stay in this role.

MAYTT: 1974 was an eventful year for Aikido and Koichi Tohei – the first major split occurred and Tohei established his Shinshin Toitsu Aikido. How aware were you of the politics of the split and were the details of the event ever fully discussed to you and your peers?

CC: I began my training on Maui in 1974. It was not long after that I began hearing the story from Suzuki Sensei himself, who had been in Japan and present during that time and accompanied Koichi Tohei Sensei to the resignation meeting with Kisshomaru Ueshiba Sensei and Kisaburo Osawa Sensei, a senior instructor with the Aikikai at the time. It was very important to Tohei Sensei and therefore to Suzuki Sensei, that everyone in Hawaii clearly understand Tohei Sensei’s reasons for leaving his responsibilities at the Aikikai Honbu.

Here is the story as told to me by my teacher, Suzuki Sensei, who was there:

It was well known at the time that Koichi Tohei Sensei was O-Sensei’s favorite student. He was the first ever to be given 10th (tenth) dan by O-Sensei, and of course was the one selected by O-Sensei as the Chief Instructor of the Aikikai Honbu in Tokyo. Tohei Sensei was clearly a charismatic and dynamic teacher who was able to spread the teaching throughout the world, not just to Hawaii. It was he who introduced Aikido to most of the areas of the world in those early years.

O-Sensei neared the end of his life in 1969. The tradition in Japan is that, with any martial art school, the status and the financial value of that school stays within the family. As in most societies at the time, this kind of asset passes to the oldest male heir. And in this case, O-Sensei´s son, Kisshomaru Ueshiba was to receive the school from the hands of O-Sensei when O-Sensei passed on. Even though Koichi Tohei Sensei was married to O-Sensei’s daughter, Kisshomaru Ueshiba was the son, so he must inherit. So, on his deathbed O-Sensei called Tohei Sensei to his side and asked Tohei Sensei to promise to honor his son, Kisshomaru, as the titular head of the school. Tohei Sensei would retain his title of Chief Instructor, and as such would oversee all instruction. But because Tohei Sensei was so well liked and had such a following outside of Japan as well, O-Sensei was concerned that the school would end up going to Tohei Sensei, and he didn’t want the school to leave his family. He made Tohei Sensei promise that he would allow Kisshomaru Ueshiba to maintain his position as head of the school. Tohei Sensei promised his teacher that he would not get in the way of that and would just continue as Chief Instructor.

However, soon after O-Sensei died in 1969, the new methods that Tohei Sensei had developed from his personal training, as well as his understanding of mind and body unification which he considered to be the secret of O-Sensei’s great abilities, began to be resisted by Kisshomaru Ueshiba Sensei. He asked Tohei Sensei not to teach using his principles of relaxed Ki movement in the Hombu Dojo. Tohei Sensei very much loved the original Aikido school, and loved his brother-in-law, the Doshu, and wanted to stay, but the Doshu was more and more forcing him into a rigid straight jacket of just presenting the movements in the way that the Doshu felt O-Sensei had done, and not in any way passing on his understanding of what is behind these movements. So, this became more and more difficult and problematic. And finally, Tohei Sensei agreed, “All right, I won’t teach the principles of Ki here, but start my own school on the side. I will only teach aikido techniques here.” Then he made a new school which he named Ki no Kenkyukai. And many of the students then from the original school would learn Ki Principles with Tohei Sensei and would come back later in the day and train aikido at the Aikikai Honbu.

Naturally, as time went on, these students training in Ki no Kenkyukai were becoming obviously very different in their approach to the practice and in their movement. And of course, then all sorts of difficulties began to arise between the students who practiced one side and those who practiced both sides. And it began to form a very distinct separation between the two camps, Tohei Sensei’s students and those feeling loyal to the original school.

At a certain point in 1973, my teacher Shinichi Suzuki Sensei, who was training with Tohei Sensei in Japan at the time, and Tohei Sensei went together to a meeting with the Doshu and Osawa Sensei, a leading figure in the original Aikikai school. They sat together at a table facing each other, and Tohei Sensei announced to the Doshu that he was resigning his position as Chief Instructor and would form his own Aikido organization under the umbrella of Ki no Kenkyukai, and it would be called Shinshin Toitsu Aikido, which means “Mind Body Unified Aikido.” That was the beginning of the kind of Aikido we practice today, which many call Ki-Aikido.

MAYTT: Since this split from the Aikikai in 1974, how do Ki-Aikidoka discuss and refer to Tohei’s time with both Morihei Ueshiba and the Aikikai?

CC: I would say that depends largely upon the teacher of the Ki-Aikido school you might look at. In my case, because my teacher was Suzuki Sensei, and he remained very close with many of the Aikikai teachers throughout the years, I learned to respect them as he did, and so in the Shunshinkan Dojo on Maui we have nothing negative to say about the events that occurred so many years ago.

In Hawaii, even though I make a point of opening my seminars to everyone, very few from the Aikikai have ever ventured into one of my seminars. On the other hand, when I teach in Europe, we have Aikikai, Aiki-Budo, Yuishinkan, and Ki-Aikido all participating together on the mat with good will.

I will tell a short, related story. When O-Sensei came to Hawaii in 1961 to visit all the schools that Tohei Sensei had established, a twenty-year-old young man named Nobuyoshi Tamura accompanied O-Sensei as his otomo. Later, Tohei Sensei sent Nobuyoshi Tamura Sensei to France to teach, and he became a well-known instructor there. Because they had trained together in Japan, and because of the time they spent together in Maui and generally in Hawaii throughout O-Sensei’s visit, Suzuki Sensei and Tamura Sensei became close friends, and remained so through the years, writing regularly, and visiting each other when possible. When Suzuki Sensei was too old to travel, and I was teaching twice a year in Europe, Sensei asked me to visit his old friend, Tamura Sensei, in southern France, which I did.

Tamura Sensei and I were at lunch one day, and I took the opportunity to say to him, “You always talk with such respect about our teacher, Koichi Tohei Sensei. Thank you for that. You and I have this same teacher, and yet, I know your teaching and it is completely different than mine. Why do you think this is so?” He said to me, “I know how you teach also, and I know it is not what I like. You reveal way too much to the students. If you do this, the students begin to think they already know all the secrets. Then they leave you. I keep those secrets to myself, and I have many more students than you!” And I must admit, this is true; he had many more students than I have.

For anyone who knew Tamura Sensei, (who passed away just a couple of years after our last meeting, in 2008), they must know what an amazingly kind and generous teacher he was. So please don’t misunderstand when I say that as much as I respect and admire Tamura Sensei, I would never change the way I teach to gather more students. As it is, even with the comparatively few students that train with me, there are probably too many for me to do a decent job of it. Suzuki Sensei always told me, “If you find a single student whose life your teaching has bettered, then you have fulfilled your obligation to me.”

MAYTT: Final question. Hawaii is the halfway point between east Asia and America, leading to a diverse set of martial arts and traditions. How has Ki-Aikido interacted with other art and Aikido styles since its birth in 1974?

CC: To be honest, there has been very little, if any. The split in Hawaii was very hard on those that chose not to follow Tohei Sensei. Most of those in Hawaii training in 1973 decided to stay with the only teacher they knew, Koichi Tohei Sensei, and so immediately joined Ki no Kenkyukai and Shinshin Toitsu Aikido. Of course, there were some who decided to stay with the Aikikai under the Doshu, and unfortunately, afterwards, there was quite a bit of bitterness towards Tohei Sensei and his students for leaving Aikikai and splitting up the original group.

As you probably know, this feeling prevailed throughout the Aikido world. As to what can happen with this kind of enmity, there was at least one humorous result. Suzuki Sensei was teaching a seminar in California many years ago, and at the banquet they showed us a video that someone had sent from Japan, circa 1966, showing a demonstration at the Honbu. There was clearly someone leading the demo, but all the viewer saw was a blurry spot moving around the dojo with uke flying off from this blurry spot in various directions! [Laughs] Tohei Sensei had been very carefully air-brushed out of the video.

Once again, Suzuki Sensei maintained good relations with many of those who remained in Aikikai and always taught me to be sure to remain open to all, no matter what their affiliation. To me, this is the very essence of the teaching of Aikido – “The Way to Union with Ki of the Universe.”

Otherwise, what would we be practicing?

MAYTT: Thank you again for joining us! This was a great conversation!

CC: Thank you again!